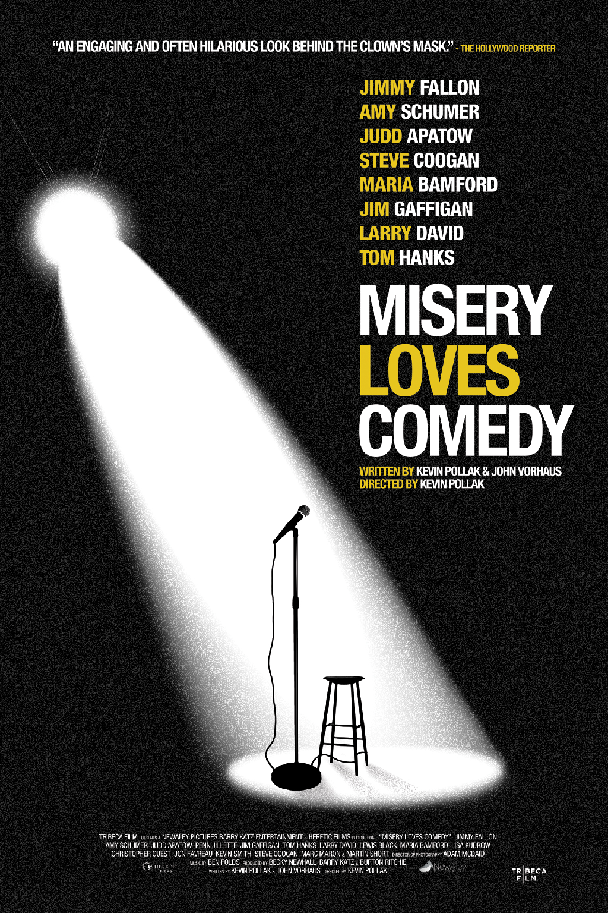

People often strive to become rich and famous, as they equate achieving a high level of success to being endlessly happy and content in life. But often times the comedians who attain the biggest accomplishments in life still struggle with their own despair, but have luckily found a creative outlet that allows them to relatably express their suffering with audiences. That continued battle of trying to achieve and maintain happiness, even after you found triumphs in your life, is intriguingly explored in the new documentary, ‘Misery Loves Comedy.’ The film, which is now available on iTunes and VOD, and is playing in select theaters nationwide before expanding to more cinemas during the rest of this month, marks the feature film directorial debut of actor and comedian Kevin Pollak.

‘Misery Loves Comedy’ features interviews with such famous comedians as Jimmy Fallon, Tom Hanks, Amy Schumer, Judd Apatow, Lisa Kudrow, Larry David and Jon Favreau, who discuss their life experiences and inspirations that led them to become interested in pursuing comedy as a career. The actors and filmmakers also offer a hilarious twist on the age-old truth that misery loves company, and how the anguish they contended with throughout their lives afforded them with the natural intuition to amusingly tell jokes. The in-depth, candid interviews and anecdotes not only reveal the comedians’ unique paths of devoting their lives to making strangers laugh, but also their deep desire to connect with audiences.

Pollak generously took the time to sit down for a roundtable interview at The Smyth Hotel in New York City during the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival to talk about writing, directing and editing ‘Misery Loves Comedy.’ Among other things, the filmmaker discussed how he became involved in making the documentary after one of its producers, Becky Newhall, approached him with the idea about making a film about stand-up comedians, specifically those who suffer from clinical depression; how he crafted the themes that appeared in the documentary by interviewing people who were living the subject, and asking them questions that would potentially illicit a conversation in the areas he wanted to focus on; and how overall he focused on the idea that misery is a universal, unavoidable human condition, and how every artist has to figure out a way to articulate their own personal misery into a story that the audience feels shines a light on what it means to be human.

Question (Q): You made your feature film directorial debut with ‘Misery Loves Comedy.’ What was it about the subject of misery within comedians that convinced you to helm the movie?

Kevin Pollak (KP): The subject of misery within comedians was the idea of Becky Newhall, who’s one of the financiers on the film. She was developing the idea of making a documentary about stand-up comedians, specifically those who suffer from clinical depression. She then spoke to my producing partner, Burton Ritchie. He and I were already developing a script for me to direct. But when those two spoke, Becky shared her idea with him, as well as the film’s title, which was her idea. Since he knew I wanted to direct, and that I was booking the talent, and honing my interview skills for five years for my internet talk show, and also had experience in stand-up, it made sense that I would be the one to guide this project into the next phase.

Q: What was the process of putting together such an impressive roster of comedians you would interview for the film?

KP: I would suggest to any filmmakers out there who are wondering how to book famous people to give interviews for their movies to not pay them. That’s the best way to get them, because then you don’t have to deal with agents, lawyers and managers; you just have to get them to sign a release. If they like you and the subject, then they’ll show up. It could be reduced to being that easy.

Or it could be because I went out to everyone who I had spoken to while doing the chat show for five years, as well as through my stand-up, who have chosen to live and die through their audiences’ reactions. I also reached out to actors and filmmakers.

We had to start treating it like a film shoot at some point. We shot for four consecutive five-day weeks. Whoever was available during that time was who we interviewed. We originally had 25 people lined up before we started shooting, which I thought would be perfect for an hour-and-a-half movie. But then people kept saying yes, and by the end of filming, we had over 60 people talking for over 70 hours. It was a difficult task to edit 70 hours into 94 minutes, which I mostly did on my own.

Q: Having interviewed so many people for the film, was there anyone who surprised you with their level of insight?

KP: Yes. The reason why John Vorhaus was given a writing credit along with me was because he helped put together some questions. The questions were all the writing that was done. I wrote a lot of questions, and he wrote some, and we put them together. From those 40 or 50 questions, I could put together the conversations, but I had no idea what answers were coming.

I knew from my experience interviewing people on the chat show that if you do you research-I had a research producer who fully researched the subject-that you could get better conversations. I interviewed people who were living the subject, so I had to ask questions that would potentially illicit a conversation in areas I ultimately wanted to be in the film. But whatever they chose to share was in their control. So I was constantly surprised and thrilled by what they discussed.

Q: There is a sense of tragedy to the film, as you dedicated it to Robin Williams. Did you have a chance to interview him?

KP: If I interviewed him, I would have included it in the film. Like I mentioned, we had four consecutive five-day weeks, but he wasn’t available during that time, as he was filming his TV show. He was shooting the same exact days for 12-14 hours. But we spoke on the phone twice during those four weeks, for almost an hour each time, because he didn’t want to get off the phone-he wanted to keep talking about the subject, and what it meant to him and me, and what he thought this film could be. He had been a mentor and friend of mine since I was 20.

He passed away while I was editing the film. My producers asked if I wanted to get a crew together and interview comedians who are in the film about how they feel about his passing. They suggested we include it in the film, as it relates to the subject. But I felt that was too manipulative, and would take advantage of a horrific situation. So dedicating the film to him just became the obvious choice, not only because of his tragic passing, but also what he meant to me, comedy and fans of comedy.

I also had to make sure the film wasn’t a biopic about any one performer, and their journey into darkness. I instead wanted to focus it on the pursuit of comedy, and the articulating of misery. That, to me, is a more interesting story than what cause someone to become addicted to drugs and die. I would rather listen to incredibly funny people talk about their experiences of misery, and their path of finding a way to entertain people. I felt I could better articulate the abilities of all performers by not focusing too much time on any one person.

SY: Since you also made your editorial debut on the documentary, did you have any restrictions on what you could include in the final version of the film?

KP: Having the 70 hours of footage made the editing process extremely difficult, and I don’t wish the process on anyone. I had an epiphany when Freddie Prinze, Jr. was talking about his dad for the first time on camera. My better half, who’s the head writer for the chat show, has a genius level for attention to detail. I said, “Let’s put you in front of your computer with your headphones on. When I’m doing the interviews, take notes, particularly with keywords, and put the time code next to them.”

So then when I was later going through the 70 hours of material, I had the time codes and keywords I could refer to. That allowed me to hone in on similar keywords from various people. For example, they would talk about how their families didn’t support them, which later turned into a chapter in the film.

Before the chapters were established, the footage had this non-linear flow that didn’t have any story or narrative. As the film grew, I realized that without some kind of narrative, the film wouldn’t have as much of an impact. As we were crafting the chapters along the way, there were a lot of moments that were depressing, insightful and hilarious, but no longer fit into the narrative. I feel the best comedic and tragic moments are included in the final version of the film. But there are still hours I consider to be provocative and hilarious.

Moving forward, we’re thinking of creating a series of pieces, whether they’re five or ten minutes. So we may create ten or 20 episodes, depending on what we want to include. That makes more sense than including random bits on the DVD. I feel like there are new ways to entertain with this extra content than including them on the special features section of a DVD-they don’t really serve the audience or filmmaker anymore.

Q: Now that you have acting and directing experience, do you prefer to work in front of, or behind, the camera?

KP: I liken that question to the one of whether I prefer to do comedy or drama. I prefer to do both, and I can’t choose one over the other. What came from my directorial debut is something that people are enjoying, which is amazing. It’s great that the Sundance Film Festival deemed worthy. The fact that Tribeca Film bought the movie before it debuted was also amazing. Now I’ve been asked to direct a comedy script that’s being developed. That offer came from the value of this film, and my work as a filmmaker.

This is all such new territory to me that I can’t choose between directing and acting. I have been asked to direct on a few occasions over the years, especially after ‘The Usual Suspects’ came out. We all had extreme street cred in the indie world, whether it was acting, directing or writing.

I developed a tremendous respect for the task of being responsible for everything, and working with department heads, but it seemed like way to much work. The actors are afforded a life, but it seemed like the filmmakers didn’t have a life at all. It takes a year of your life to make one film, which seemed daunting.

I’ve also been asked to do Broadway a couple of times, but they wanted a nine-month run. I can’t say the same words in the same order for eight shows a week for nine months. The first three months would be the greatest experience of my life-I’d think, “I can’t believe I’m on Broadway! People care, so this is amazing!” During the middle three months, I’d think, “This is still pretty good.” But during the last three months, I’d hate it.

So I didn’t have the need or desire to live with the same material and project for a year. I’m not a control freak, and that seemed like an important aspect of directing, too. But spending nine months in a vacuum at an editing bay that I created on my own in my dining room taught me the whole process. I worked with two-time Academy Award-winning visual effects supervisor, Robert Legato, who won for his work on ‘Titanic’ and ‘Hugo,’ while editing the documentary. He’s worked with Martin Scorsese on all of his films since ‘The Aviator.’

Robert is a genius and a pal, and we were talking on the phone when I mentioned that I was going to make this film. He said, “Let me know how I can help,” and I said, “You’re an editor, so please help me edit.” When he said yes, that allowed me to create a 10-minute teaser for the film, which acted like a template for the film.

We shot the film in September and October of 2013, and by the Sundance Film Festival in 2014, the financiers asked me for a 10-minute teaser to show to other potential investors. So that was a gift, because it forced us to make something from our 70 hours of footage. That process was really fast, and the teaser didn’t feature any real story-we had one person finish another person’s sentence. That helped the teaser become funny and entertaining.

Then Robert was about to direct a movie, so I had to let him go. So he showed me the basic steps of how to cut on Adope Premiere. I learned how to use two screens to create bits, and then went out on my own. I expanded the 10-minute treatment, and the film eventually became so big I had to create the chapters. I had to create the narrative on my own, and showed it to people, and then made some adjustments. I really learned about that process of filmmaking through editing on my own.

Every director I have ever worked with and spoken to has insisted that editing is the final rewrite. I’ve been a member of the Writers Guild as a storyteller, be it stand-up or screenplays, since 1987. But I’ve always known it’s all about the editing and rewriting processes.

Q: The movie sets out to answer the question that you have to be miserable to be funny. But a lot of the people you interviewed are rich and famous, but they still are contending with their misery. So were you asking the question, does money buy happiness?

KP: Money buys expensive misery. The benefit of the film is that it forced me to focus on the idea that misery is a human condition. It’s unavoidable, and is one of life’s few guarantees. It should be next to taxes and death as an unavoidable fate-every human being will suffer. The artist, whether a painter, singer-songwriter, sculptor, comedian or filmmaker, has to figure out a way to articulate their own personal misery into a story that the audience feels like shines a light on what it means to be human.

The films shows that comedians can articulate their misery through their own point-of-view. The movie also shows who are these people who have chosen to do this line of work, and what is their misery, as well as their path and conclusion.

When the producers asked me to be on camera, I thought it was a little self-serving. The editing is my opinion about having to be miserable to be funny. You hear me ask some of the questions, so you get the sense that I’m in the room. I didn’t want to be tricky about who’s asking these questions, even though it would be obvious at some point.

I did turn to Lisa Kudrow during her interview and said, “Ours is the only profession that people can try at anytime, if they choose. But you don’t see any at a party try to dabble in dentistry. But they can try to tell a joke, if they want to do so.” I feel like the one thing that diminishes comedy is that everyone feels like they can kind of do it.

So there were a few instances where I was heard on camera. But I wanted to get as many hilarious, creative and miserable people as I could, and have the audience get to know them in the first two acts. Then I wanted to pose this question to them about whether you need to be miserable to be a comedian during the third act. That way the audience can have an emotional connection with them before we asked the question. I wanted to include their humor and humanity all the way until the end of the film.

Q: After making ‘Misery Love Comedy,’ are there any other topics you’d like to make a documentary about in the future?

KP: I don’t know about continuing with the documentary style-it was so hard. Being given this very recent opportunity to direct a comedy film has been very enthralling. There’s also a suspense thriller that I wrote that’s been developing for awhile. They’re the next two projects that I’ll direct.

I feel like it was beneficial to direct the documentary first, just so that I could gain that editing experience. That process is where the story and narrative is created. But documentaries are way too daunting to return to anytime soon.

Written by: Karen Benardello