Title: LEVIATHAN

Cinema Guild

Director: Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel

Screenwriter: Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel

Cast: Brian Jannelle, Adrian Guillette, Arthur Smith, Asterias Vulgaris, Callinectes Sapidus, Christopher Swampstead

Screened at: Review 1, NYC, 2/13/13

Opens: March 1, 2013

When Fathers’ Day rolls around, you look at some of the greeting cards and you’re likely to find an equal number of Mallards and of dads chatting with their children over fishing rods. Vacation signs pop up on stores over the summer stating “gone fishing,” considered the thing to do when your years at work are over. This is fishing as metaphor for bonding, for vacations, and for retirement. Catching the big one is a popular sport wherever streams and rivers exist. It’s a romantic image. By contrast, though, consider Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s “Leviathan” (the name, meaning “whale” or “sea creature” taken from the Book of Job 41 ????????? and mentioned in Isaiah 27).

This documentary is unlike any other, which is not necessarily a good thing. Absent an interview with the directors (Lucien Castaing-Taylor who is British born while Véréna Paravel is French), one can conjecture that the main point of the movie is not to instruct the movie-going public about where they their Friday dinners came from—like, for example, an elementary school film about “your friendly postal employee” or “how your bread is baked”—but an attempt to show off the expertise of the filmmakers, who direct the use of dozens of waterproof cameras strapped everywhere not only on the workers but on the decks and hulls and cranes. That is an exemplary achievement in cinematography but not one that translates to entertainment, unless audience members are hip to the subtleties of soundtrack and painterly images of seagulls.

The men aboard a trawler on the stormy seas off New Bedford, Massachusetts, are of the macho variety: tattooed (one with a full image of a naked woman on his man-sized left arm), cigarettes dangling from their lips, speaking to one another over microphones to overcome the sounds of the raging sea and the blurts of the gulls and the movement of chain-nets and other equipment to haul in the catch.

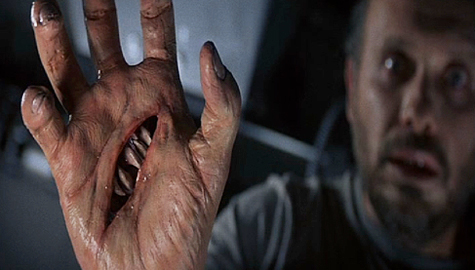

Though the men do not use worms for bait, opting simply to drop the huge nets into the sea, the fish don’t stand a chance. They are hauled brutally up, bloodied, beheaded, some sliced in half, the gestalt covered by the eager cameras from every angle. During the first twenty-five minutes or so, an audience cannot be blamed for wondering what’s going on. In fact if people in a film course did not know that the action takes place within a trawler all photographed to honor the three unities of time, place and action, they could take guesses, stop the film, and discuss their conjectures.

The filmmakers zero in on extreme close-ups of the men, in one long take honing in on one fellow who sits in the trawler’s cafeteria with a cup of coffee, staring blankly at a TV screen that in addition to fishing news discusses the power of a laxative in a commercial—until the guy falls asleep, and he’s not acting. Aside from repetitive looks at the huge bundles of fish caught in a net that is really a series of chains, the most dramatic event within the New England darkness is the cutting of a flat fish: one fisherman grabs onto the fish with a hook, the other follows suit and slices the poor devil in half.

Since there is no narration on the soundtrack which features an audio from “Sweetgrass”’s Ernst Karel, we must allow the pictures to tell all. Here again, there is no step-by-step illustration of how the fish are caught, a feat that would require some underwater photography, but there is reason to believe that the directors without consciously realizing that they are putting forth an imitation of last year’s surreal movie, “Samsara,” eye candy that takes its audience to twenty-five countries without the hassles of the airport. Though we are spared the seasickness, the hard work, and the brutality of the job of these men, sitting in our comfortable seats and watching what is essentially paintings in motion, we might consider ourselves stuck for eighty-seven minutes undergoing the suffering of Job, an innocent man who considers himself trapped in the hands of Satan. The movie has no commercial prospects and might be appreciated by those with an acquired taste, one requiring even more discipline than an appreciation for caviar.

Unrated, 87 minutes. © Harvey Karten, Members, New York Film Critics Online

Story – C-

Acting – C

Technical – B-

Overall – C