Title: Dear Mr. Watterson: An Exploration of Calvin & Hobbes

Director: Joel Allen Schroeder

A big-hearted but overly fawning documentary about the impact of the popular newspaper comic strip of the same name, “Dear Mr. Watterson: An Exploration of Calvin & Hobbes” is a fans’ document that can’t see the forest for the trees. The success of first-time director Joel Allen Schroeder’s film — Kickstarted by more than 2,000 online benefactors — lies in the many other cartoonists he corrals to talk about the hermetic Bill Watterson. The problem is that Schroeder has nary an idea of how to structure his movie, or push beyond surface intrigue to more deeply examine the relationship between artist and art. The result is a curio that fans of the strip will still likely embrace, but in large part feels just like a wasted opportunity.

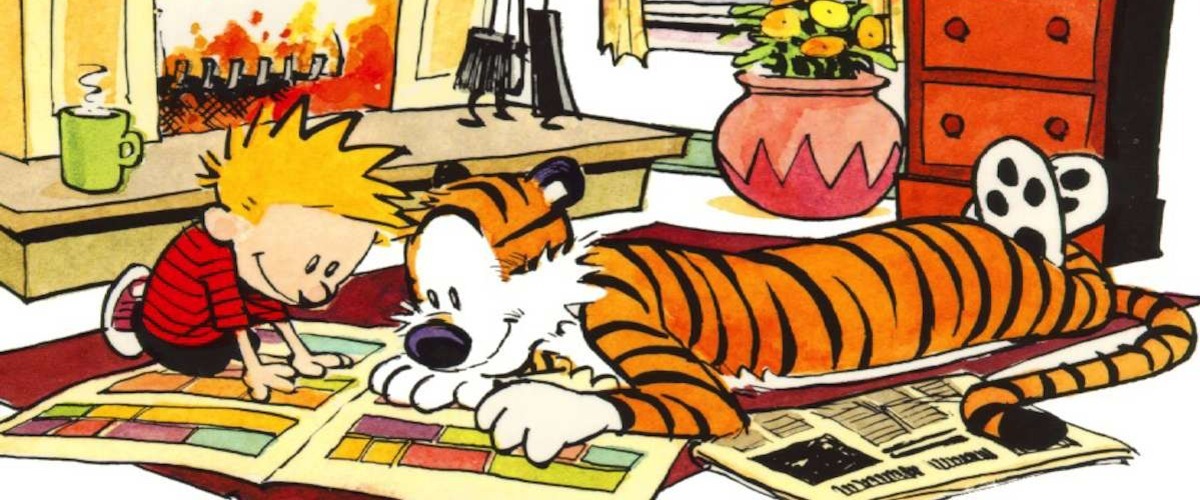

Calvin and Hobbes, for those in need of a refresher, debuted in November, 1985, centering around the adventures of a rambunctious, imaginative six-year-old and his pet tiger Hobbes — a stuffed animal in the eyes of the adults in his life, but a loyal, intrepid and very real companion to young Calvin. Contrasting his characters’ worldviews (their namesakes were Protestant reformer John Calvin and philosopher Thomas Hobbes, a nod to the cartoonist’s college political science degree) and illuminating the rich inner dialogue of adolescence, Watterson won fans across a broad spectrum of ages. His cartoon would become a staple of newspapers all across the country, and go on to be collected in 18 books in the United States that would sell more than 45 million copies. Then, at the end of 1995, Watterson decided to cap his pen and retire.

There’s a tension at the heart of “Dear Mr. Watterson,” and one that never quite dissipates, even if a viewer comes to accept some of its more base level, nagging shortcomings. The film, of course, rightly celebrates Watterson’s deft touch with playing adolescent fantasy against reality for humorous effect, as well as the skill of his brushwork in capturing water, trees and motion. Naturally, too, the movie traces the influences of Watterson’s work and writing — comic strips like Pogo, Krazy Kat and of course Peanuts. Yet it’s 25 minutes in before the strip’s philosophical bent is even mentioned, and Schroeder seems less interested throughout in this very real and important element than in gazing upon and pontificating about original strips in an archival library.

Thankfully, there are loads of smart people — from Seth Green, a fan, to other cartoonists like Berkeley Breathed — who sit as interview subjects, recounting the strip’s rise. “Dear Mr. Watterson” catches fire when digging into its subject’s views on licensing, about the fortune ($300-400 million, by some estimates) that he unarguably left on the table by refusing to sign over the rights to his characters for rendering unto T-shirts, lunch boxes, bed linens and stuffed animals. Charles Solomon and Pearls Before Swine creator Stephan Pastis speak most eloquently and engagingly about this topic, and one can see how the weight of this ongoing, argumentative debate between Watterson and his publisher worked its way into the strip itself, with direct commentaries about the relationship between art and commercialism.

But the interesting nature of this portion of the film only points up the strange refusal on the part of Schroeder to draw the parallel most obvious to anyone with even a cursory familiarity with Watterson’s work — that of J.D. Salinger. Both artists had strong feelings about the adaptation or rendering of their work into other media; both essentially retired following the white-hot career heat that came with the creation of an enormously popular and influential work; and both staked out intensely private lives that invited much speculation as to their intellectual and professional endeavors after withdrawing fully from public view. As the film unspools, one keeps waiting for Schroeder to address this, but he never does.

In fact, while Schroeder does trip to his subject’s hometown of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, the movie provides such scant biographical details (does Watterson have siblings? children of his own?) as to render it almost completely ridiculous. There’s respecting a subject’s privacy (there’s obviously little chance Watterson was going to reverse decades of habit and submit to an interview here, having given only two since the cessation of Calvin and Hobbes) and then there’s going out of the way to even avoid even mentioning the elephant in the room, and it’s the latter that makes “Dear Mr. Watterson” feel like such a cop-out, and soggy toss-off.

Technical: B-

Story: C+

Overall: C

Written by: Brent Simon