Title: Lenny Cooke

Directors: Josh Safdie, Benny Safdie

Steve James’ superb documentary “Hoop Dreams” set the bar for complex examinations of high school basketball players with lofty aspirations of making it to the NBA. But of course just as new dreams of playing professional basketball are realized each year, more are dashed against the shoals of cold, hard reality. A sobering if terrifically frustrating look at a kid who went from can’t-miss to never-was arrives in the form of “Lenny Cooke,” a nonfiction film about the same-named, top-rated teenage hoops prospect, a contemporary of Carmelo Anthony and LeBron James, who maxed out his high school eligibility early and then spurned college scholarship offers in an ill-fated decision to declare himself available for the NBA Draft. A dreary, jumbled first hour gives way to an electric last 30 minutes in which co-directors Josh Safdie and Benny Safdie’s film finally gets real, and taps into a torrent of anger and regret.

A good portion of “Lenny Cooke” unfolds in the wake of the 2001 NBA Draft, in which high schoolers dominated the first round lottery selections and 19-year-old Kwame Brown was selected with the top overall pick. A bouncy Brooklyn swing forward who averaged 25 points, 10 rebounds and a couple steals and blocks during his junior year of high school, Cooke is at this time being heavily recruited by all the universities with top basketball programs. As he plays at various summer camps against the other top competition in the nation, he also has to decide whether he wants to forgo college a year hence and enter his name directly in the NBA Draft. An additional wrinkle occurs when he turns 19 halfway through his senior year and, owing to New Jersey state athletics rules, is unable to compete any further with his high school team. Cooke moves to Michigan to get his academics in order and eventually opts to declare himself draft-eligible, but is then not selected by any team. He spends subsequent years bouncing around various international and semi-pro leagues.

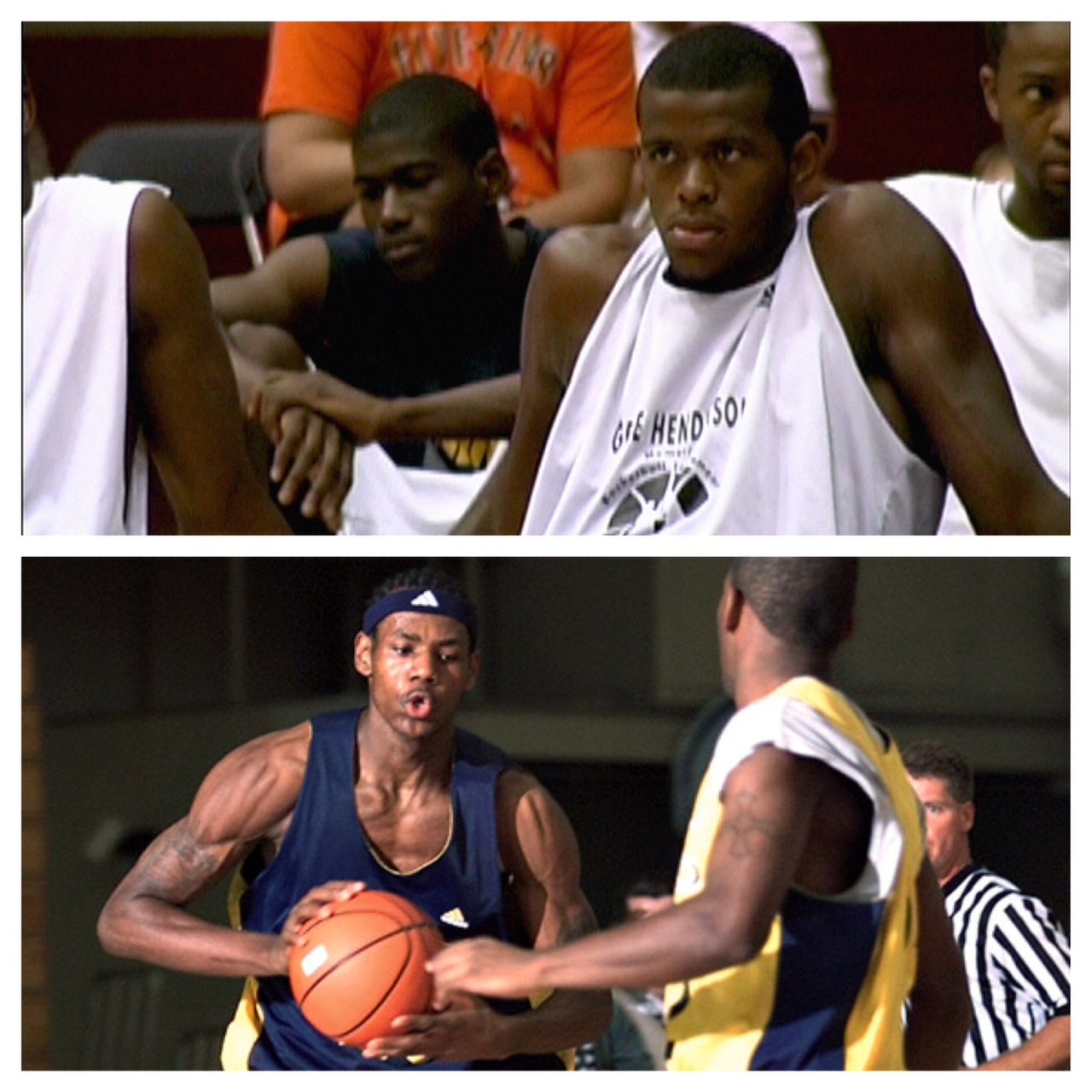

Few movies turn on a dime as dramatically as “Lenny Cooke.” The first two-thirds of the film is interesting only insofar as inveterate hoops junkies might find fascinating grainy amateur footage of two AAU teams featuring Cooke and the aforementioned James dueling against one another, or a young Kobe Bryant, six years removed from the draft himself, talking to Cooke and high schoolers about the NBA. The Safdie brothers may have the benefit of some rare extant footage, but they have absolutely no idea how to shape it into an interesting narrative, and their refusal to supplement old interview material with any sort of modern-day contextual analysis lowers “Lenny Cooke” into a swamp of yawning myopia.

The bulk of the movie’s first hour is comprised of footage accrued by producer Adam Shopkorn, who at the time was an aspiring filmmaker just out of college. So it’s basically lots of indulgent, formless hamming it up between Cooke and his friends, and then game footage and some chats with Cooke’s legal guardian, plus a couple hoops coaches and industry hangers-on, like Adidas peddler Sonny Vaccaro. Is there well constructed biography? No. A cogent explanation of why Cooke ended up living with a white woman in New Jersey instead of his biological mother and siblings? No. Any illumination of the collegiate recruiting process? No.

Then, rather than explore why or how — in the eyes of hoops experts — Cooke failed to even get selected in two rounds of the NBA Draft, the film instead transitions from that heartbreak straight into… three or four minutes of footage of Cooke playing for the Pennsylvania Valley Dogs and other assorted sub-NBADL squads. Bafflingly, it’s 58 minutes in before “Lenny Cooke” pivots to something approaching present day, in the form of a 2012 interview between Cooke and a New York newspaper reporter.

It’s here, when one has almost completely written off “Lenny Cooke,” that it catches fire. An out-of-shape and engaged father of two living in rural Virginia, Cooke isn’t necessarily the most reflective and articulate about his situation. But at a sad 30th birthday party, where he gets buzzed and upon returning home watches the guys he competed against in high school now on television, the movie finally gets real. Cooke lets loose on friends he feels never make an effort to visit or contact him. Later, he talks about playing basketball not for an abiding love of the game but just as a means to make friends and get money and sneakers, and laments, “They made me this person — my name is Leonard, and you ain’t never heard anyone in the basketball world call me Leonard.”

It’s utterly arresting, this home-stretch segment, which also includes a clever, effects-enabled gambit by which present-day Cooke delivers life lessons to his teenage self. And yet it’s also a case of too little, too late. Whether too intimidated by their subject or just pathologically incurious, the Safdies are not intuitive filmmakers. When Cooke makes mention of accepting $350,000 from an agent — an act which would have scuttled his collegiate eligibility, and thus possibly have influenced if not explained an entire chain of decisions and consequences — there is no interruption or follow-up, no attempt at clarification. “Lenny Cooke” is lazy, fly-on-the-wall filmmaking — a mere glancing, refracted illumination of its subject — for a story that deserves a lot more.

Technical: D

Story: C-

Overall: C-

Written by: Brent Simon