Bravely refusing to allow aggressive political leaders abrasively dictate the actions you take, as you strongly support people’s right to choose, is an admirable trait not everyone possesses. But when a person defies intimidation, and willingly puts their life on the line to support those freedoms, a much needed revolution that progresses those liberties is often the result. That courageous struggle is admirably showcased in the new biographical drama, ‘Rosewater.’ The film is is based on the true story of how journalist Maziar Bahari relentlessly reported the violation of Iranian citizens’ right to vote in 2009, even though his actions led him to be imprisoned and beaten by authorities for months. His determination is enthrallingly chronicled in the feature film writing and directorial debut of ‘The Daily Show’ host, Jon Stewart.

‘Rosewater’ follows the Tehran-born Bahari (played by Gael Garcia Bernal), a 42-year-old broadcast journalist with Canadian citizenship living in London, as he returns to Iran in June 2009. The reporter set out to interview Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the prime challenger to controversial incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. As Mousavi’s supporters rose up to protest Ahmadinejad’s victory declaration hours before the polls closed on election day, Bahari endured great personal risk by submitting camera footage of the unfolding street riots to the BBC. He was soon arrested by Revolutionary Guard police, led by a man identifying himself only as “Rosewater,” who proceeded to torture and interrogate the journalist over the next 118 days.

The following October, with Bahari’s wife, Paola Gourley (Claire Foy), led an international campaign from London to have her husband freed. In the process, she received support from Western media outlets, including The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. As she continued to keep the story alive, Iranian authorities release her husband on $300,000 bail and the promise he would act as a spy for the government.

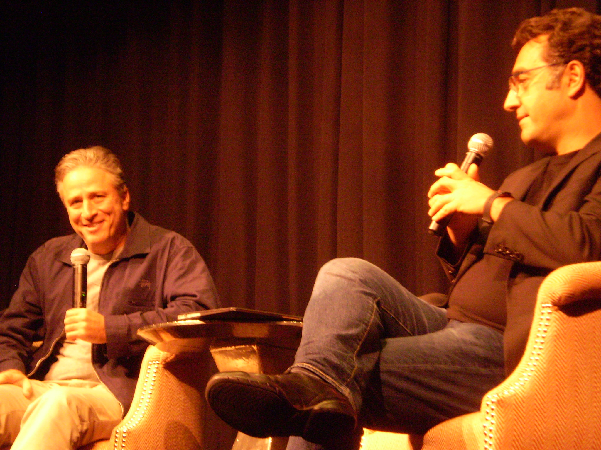

Stewart and Bahari generously took the time to talk about filming ‘Rosewater,’ which is based on the reporter’s 2011 memoir, ‘Then They Came for Me,’ during a recent press conference at The Crosby Hotel in New York City. Among other things, the filmmaker and journalist discussed how Stewart is somewhat worried how the Iranian government will perceive the film, but realizes that he can’t control how other’s react to his work; how professional journalists are having a more difficult time accurately and sufficiently doing their job, because citizen journalism is on the rise, but how the latter is helpful in quickly spread news on the Internet; and since Stewart is a first-time filmmaker, it was beneficial that he already had a script and a timeframe he could shoot the drama in when he approached financers.

Question (Q): How did you both come together to adapt your memoir, Maziar, ‘Then They Came for Me,’ into the film?

Maziar Bahari (MB): What happened, basically, is when I came out of prison, I went on ‘The Daily Show.’ After that, we became friendly, and we talked about doing a film. Jon wanted to be a producer on the film. We of course talked to people, and some people were either busy or not interested-

Jon Stewart (JS): -in being paid to write, and what we were going to do. (laughs)

MB: Exactly. I think after about year-and-a-half, Jon just said we cannot wait, and it had to be done. He started to write the script, which we collaborated on.

Q: How were people like J.J. Abrams involved with the script?

JS: We had a few directors who had come on ‘The Daily Show,’ and I would sneak back into the green room and be like, “Soooo…” But they’re friends of mine that were generous enough to read it, more to give me a sense of the viability of it. So that they could just look at it and say, “Yeah, you know what, you’ve got a viable project here,” rather than more specific notes or anything.

Q: Jon, were you nervous about making this film considering how the Iranian government treats journalists?

MB: I think he’s going to keep it a secret. (Laughs)

JS: Good point! I mean I’m nervous when the weather changes, so that’s a general state of being and lifestyle that I’ve embraced. You can’t control how people see your work or what their reaction is to it. I’ve learned a long time ago that you can’t outsmart crazy. So, you do your best work with the most integrity you can. You tell the story in its finest iteration, and hope that it’s perceived in that way.

Q: How did you go about choosing the moments to let the humor shine through?

JS: So much of that is organic. You can’t impose that on the story; the humor comes from how absurd the reality of the situation was. Maziar’s not a spy. He’s done nothing wrong, so they’ve got to create this scenario that implicates him in some way. There is an absurdity that regimes have this monopoly on the truth. So, we tried to capture that, because it’s from the book. Maziar’s ability to recognize that as he was being held was one of the most marvelous things of his memoir. So, trying to capture that in its natural state, as opposed to imposing it on the film, is where I tried to go with it.

Q: Given that journalism is a somewhat endangered profession these days, is there something you were trying to convey with this film that make people appreciate more journalists and the risks that they sometimes take?

MB: I think journalism is going through a very difficult time in (its) history, especially professional journalism. But I think journalism as a whole is becoming more invigorated. Yet professional journalists are having a more difficult time getting paid, because citizen journalism is on the rise. It’s not only in this country; it’s all around the world that citizen journalists are replacing professional journalists, and information is becoming more democratized.

I think what the film shows is the importance of citizen journalism around the world. One of my favorite shots of the film is that little boy filming the destruction of the satellite dishes, which shows how these governments can create all these obstacles and barriers in the way of professional journalists. Then little Mozart of citizen journalism comes along, and films it, and just puts it on Facebook, or YouTube or Twitter, and shares it with the world.

Q: Jon, it’s well known from The Daily Show that you have a complicated relationship with the 24-hour news cycle, and cable news in particular. But this film shows a very euphoric approach to the social media news cycle, as well as other communications in the 21st century. Could you talk about your opinion on that and how you wanted to showcase that as a filmmaker?

JS: Well, I think it’s important-you can be critical of things that are not holding up the ideal of what you might imagine journalism to be. But then at the same time, it’s important to demonstrate what that ideal might be. Because places are cutting back on the finances of journalists, and now a lot of them are out there without the infrastructure and support of these big news organizations; they’re freelancing, and they’re on their own.

Then you look at a case like James Foley. This was a guy that wasn’t kidnapped by ISIS; he was kidnapped by locals, and they sold him to ISIS. It’s the type of situation that you are in great peril, and you don’t know where it is. It’s all for the hope of capturing things that are happening in parts of the world that you think people should know about.

That’s something that should be revered, protected and honored-criticism comes from a feeling of disappointment in an ideal. When you recognize that ideal, I think it’s important also to highlight and celebrate it. You should also try to preserve it, and protect those who are risking so much to bring it.

Q: Going back to when you were saying how viable the project was, beyond J.J. Abrams and getting to the level of people like (film producer) Scott Rudin, how quick was the process? Or was it more like people thinking, the guy from ‘Big Daddy’ wants to make a serious movie?

JS: It’s interesting you say that. There were a lot of (people saying), the guy from ‘Big Daddy’ is here.” (laughs) Whenever I would go to a movie or a restaurant, (they say) “The guy from ‘Big Daddy; wants a cheeseburger!” I think it helped that I had some profile. So, they could view it as an added value to a project like that. The director could go out and try to sell it in places, so you had that going for it, and you had this incredibly compelling story.

What also helped in our favor is that we were doing it and assembling it outside of the traditional development of a film. So, by the time I went to them looking for finance, I had a script and a timeframe that I had to shoot it in, because there was only a certain amount of time I could do being away from the show. So, I knew very specifically when it had to be done, and I already had the script, so they had clarity in terms of what their involvement would have to be. I was only in LA for a weekend!

So, it was one of those where we sort of set it up through Scott and through an agent that he works with at UTA. We said, “Send this to five or six independent financiers that you think might appreciate or take to the material. If they are interested, I’ll meet with them that weekend there.”

By the end of that weekend, we had our money and we had our timeframe. My experience with the process is that you just always wanted to be in the game at each stage. I wanted to be able to write a script that was viable enough that we were still in the game. I wanted to be able to go get enough money that we‘d still be in the game. At each stage, you just want to keep it alive.

Watch clips of Stewart and Bahari discussing ‘Rosewater’ during the New York press conference below.

Written by: Karen Benardello