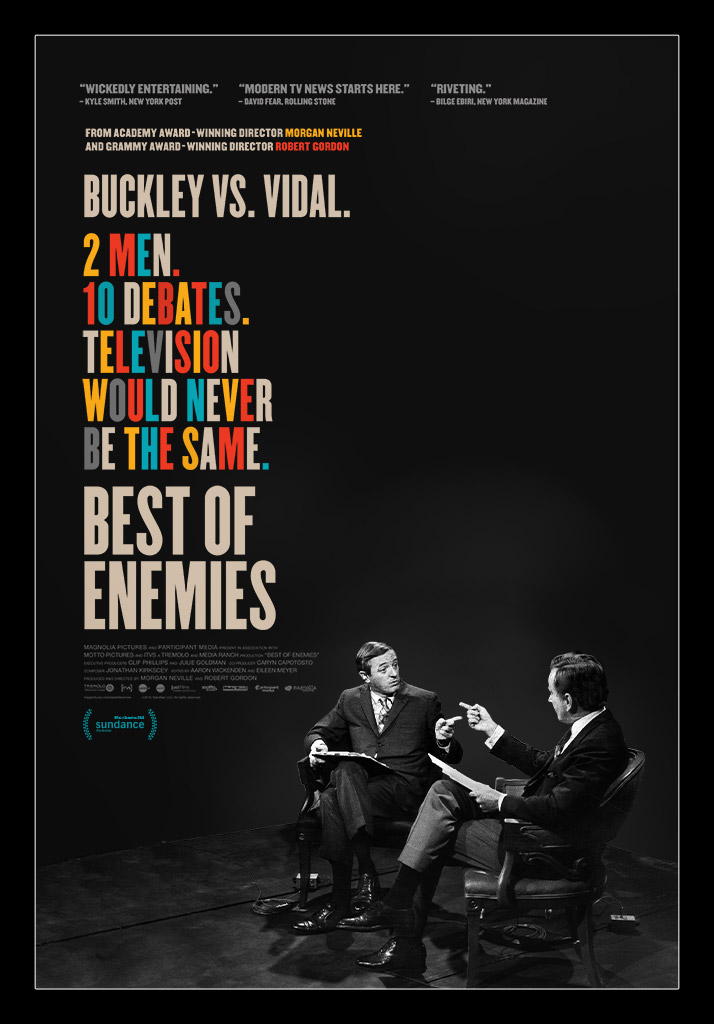

It’s not often when people are able to completely and devotedly immerse themselves in their biggest passions for both their personal enjoyment and professional gratification. But when they truly are able to indulge themselves in their strongest cultural affections, and reflect on how the views that oppose their own are impacting society, often times they’ll find fulfillment in expressing their own ideas to humanity. That personal contentment is powerfully showcased in the upcoming political documentary, ‘Best of Enemies,’ which was co-written, directed and produced by friends and occasional collaborators, Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville. The film, which is set to be released in theaters on July 31, allowed the filmmakers to finally work together in politics, a cultural subject they’re truly intrigued by, after they previously only made music documentaries together. The two were inspired to chronicle a story where the anger behind the distinct characters, political commentators Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley, continuously kept deepening, as they debated that their opposing views on society were catastrophic for America.

‘Best of Enemies’ chronicles how in 1968, ABC was last in the ratings of the three major television networks, and needed to find programming that would spark people’s interest and increase viewership. So the network’s officials decided to hire Vidal and Buckley, two towering and diverse public intellectuals, to debate each other during the Democratic and Republican national conventions. Buckley was a leading figure of the new conservative movement, while Vidal was a leftist novelists and polemicist, who was also a cousin to Jackie Onassis.

The two commentators held a deep-rooted distrust towards each other, as they believed the other’s political ideologies were dangerous for America. During each of the 10 televised debates they participated in together, the two not only argued over their ideas on political policy, but also personally insulted each other. As the unscripted live exchanges became increasingly explosive, the two eventually delved into scathing name-calling, which kept viewers riveted and led to ABC News’ ratings to drastically skyrocket. As a result, a new era in public discourse and debating on important national issues was created.

People who knew Vidal and Buckley, as well as experts who are well associated with how politics are portrayed in the media, including Vidal biographer, Fred Kaplan; Buckley’s former Executive Assistant, Linda Bridges, and his brother, Reid Buckley; William Sheehan, the former president of ABC News; and Richard Wald, the former head of NBC News and the former Vice President of ABC News, also offered their insight into how the two commentators acted towards each other, and what drove their disdain for each other.

Gordon and Neville generously took the time recently to talk about co-directing, writing and producing ‘Best of Enemies’ during an exclusive interview in New York City. Among other things, the filmmakers discussed how they became interested in transitioning into making a political documentary together, after collaborating on their music documentaries, when one of Gordon’s friends showed him a copy of the debates between Vidal and Buckley; how there were a lot of great remarks and ideas in the debate and interview clips that they couldn’t fit into the documentary, and figuring out what to leave in and cut out was one of the hardest part of making the film; and how the process of making a cinematic film out of debates between political commentators was also a difficult aspect of crafting the story, but including the biographical element about both Vidal and Buckley became an essential aspect, as the filmmakers had to explain who the debaters were to most audience members, as many people had never heard of them.

ShockYa (SY): You co-directed the new political documentary, ‘Best of Enemies,’ together, after you helmed several other documentaries together, including ‘Johnny Cash’s America and ‘Shakespeare Was a Big George Jones Fan: Cowboy Jack Clement’s Home Movies.’ Why did you both decide to shift from making musical documentaries to a political one, and how did helming this film come about?

Robert Gordon (RG): A friend of mine had obtained a bootleg copy of the debates, and shared it with me. I was blown away, and was really attracted to working with the material. Morgan and I had previously made four films together, and we also work independently. This material seemed like it would be better if we worked on it together, as I needed his expertise. (laughs)

Morgan Neville (MN): It was interesting because it’s a different way of making a film. You come across this footage, and it’s like a window into this other world. I think of the line that the past is like a foreign country. It’s another world where you have these other characters who went in front of the nation and spoke like this. I found it fascinating, but we didn’t know what the story was; we just knew that we had these rich, incredible characters.

So the process of making the film was figuring out what’s the context, story and aftermath for this. This was one of those rare projects that became better with every step. Since no one has ever written a book about the subject, it’s still so fresh. But then we had to do a lot of original research, so that we could figure out what the story was, which is why it took us five years to make. (laughs)

SY: What was the process of not only securing the clips you featured in the documentary, but also how you would edit them into the final film?

MN: I think we had a structure in mind from the beginning, in that it would be like a heavy-weight championship. Since they had 10 debates, it would be like they had 10 rounds. We didn’t necessarily go through each round, but the debates were something we would go back to, as they were escalating. We knew that in the penultimate debate, there was this explosion that we had to build to. But we had so much good material that the hardest part was cutting things out.

RG: I think we could make another 60-minute film, without repeating anything that’s in this one. All of our interviews were outstanding and full of insight, and the debates were rich with material. There were a lot of great remarks and expansive ideas that we couldn’t fit in. Figuring out what to leave in and cut out was the hardest part.

MN: I think that’s the part that comes from experience. The fact that we’ve been doing this for so long makes it a lot easier to see the great things that aren’t going to make it into the film…

RG: …and be okay with that. That’s when you know you’re doing the right work-when you take out a line that you thought for sure was going to be in the film, and you accept it. I think an inexperienced person would say, “I’m leaving this in there.” But the experienced person would say, “If I’m taking this line out, then the film is great, because I wouldn’t take it out otherwise.”

SY: As co-directors, how did you decide who would handle each aspect of the filmmaking of ‘Best of Enemies?’ How did working on your musical documentaries together influence the way you approached helming this movie together?

MN: Having worked together before certainly makes it easier. We’ve worked together several times because we agree 95 percent of the time. That last five percent strengthens the film. One of us has to argue, and justify, what we want to include that the other doesn’t initially agree on. There’s no clear delineation of who does what; you do everything all the time when you’re making documentaries. I would say there’s an unspoken division of interest. Robert gravitated more towards the raw debates, while I gravitated more towards the biographical and contextual material. Then we brought everything together, so that we could figure out what that balance was.

SY: How did you work to make ‘Best of Enemies’ visually appealing, since most of the debates and discussions between Gore and William take place in the same room?

RG: You’ve hit upon the crux of the hard part of the documentary, which was, how do you make a cinematic film out of talking heads? Our base matter was two guys who were sitting around talking. That’s where the archival research became helpful. From the time of the inception of the idea for, to actually finishing the, film was a five-year process. It was four years of development. The first thing for me was to be aware of the fact that no one knew who either man was. That meant that there was going to be a lot more biographical element than I originally thought, which turned out to be great. That became an essential aspect, as we had to explain who these men were to people who had never heard of them.

SY: How important was it to emphasize Gore and William’s drastically different ideals in the film, and what was the process of showing the clash in their personalities?

MN: I think it was essential, because as much as the debates were about politics and culture, they’re also personal. I think the reason they had such a unique animosity between them because as different as they were politically, they were also similar in a lot of ways. I think those aspects really informed who they were and where they came from, and an understanding in the stakes they felt. To me, that was a huge part of the story.

It’s also important to understand where people like that come from, in general. Our country doesn’t make people like Vidal and Buckley anymore, and our media doesn’t allow people like them to grow. So it was interesting for us to understand that, too.

SY: Do you both feel as though airing the debates on national television on ABC helped set the precedent for the debates in the modern media landscape, and how the true discussion of politics is often overshadowed by the news networks’ antics to garner more ratings?

RG: We came to view it as a turning point between the end of one era and the beginning of another one. Intellectuals aren’t on TV today, as we’re getting our news from the satirists. So the networks seemed to take away from these debates that the ratings went up when the sparks would fly. I think it’s been a downward slide until the present, as you know have commentators on TV with a producer in their ear, telling them that the ratings are going down, so get off this subject. They’re told to instead talk about whatever’s going to keep people on the channel.

SY: Do you both think the debates changed the way Vidal and Buckley also looked at politics?

MN: I don’t think the debates changed their political stances, but I do think they changed their profile in the country.

RG: The experience did stay with them, especially that moment in the ninth debate; neither of them could ever escape it. Bill always wanted to escape it, while Gore always wanted to revel in it.

SY: Both of you were journalists before you became filmmakers. How did your experiences as journalist influence the way you approach making movies?

MN: To me, documentary filmmaking is 3D journalism, as they both utilize the same skills; they’re about research, interviewing and storytelling. You’re just telling the story in a different medium. As someone who has made a lot of documentaries, and has hired people to work for me, I like people with journalistic backgrounds more so than people with film backgrounds. Often times film school teaches you to tell people what you think, while documentary filmmaking is about listening to other people. Documentary filmmaking requires a different skill. So I still consider myself to be a proud journalist.

SY: Besides helming the film together, you also co-wrote it together. What was the writing process like, including the research you did into the debates, and the questions you asked the interviewees?

RG: We worked on all aspects, as writing for documentary films is done in the editing process. But creating the questions was something I’ve always liked doing. One of us will create an initial list of questions, and then we’ll bounce it back and forth. I think that process gives us better interviews, because it gives us different perspectives before we even begin talking to the people we feature in the film.

Then we continue the writing process as we go into the editing room, which is where we have the five percent of disagreements. That’s where we have to justify what we’re doing. Documentaries are shaped by good editing. Morgan has a good line about writing documentaries-“Scripted narratives are written before you go out and shoot. But with documentaries, you do your shooting first, and then you do your writing in the editing room.” That process is much harder.

SY: What was the process of filming the documentary independently, and shooting interviews sporadically between other jobs you were working on over the course of the five years that you mentioned earlier? Did it impact or influence your directing process at all?

RG: That’s actually the standard procedure, unfortunately. I wish we didn’t have to wait four years to get it funded.

MN: Being an independent filmmaker is all about raising money. I think the biggest problem on this film was that people didn’t see the relevance in this story. They thought it was a historical footnote of two old dead men. (laughs) But now the reward we’ve been getting is that people are saying, “We can’t believe how relevant this is.”

SY: With social media being so relevant today, do you think that if it was available during the debates between Vidal and Buckley’s debates, it would influence the way they interacted with each other?

MN: It’s interesting, because snark is so common now in our culture, especially the cutting exchanges between people on such websites as Twitter. But that was unheard of in 1968, so I think that’s what made their debates so offensive and enticing. People were surprised to see others behaving uncivilly. Like what we see today, there’s something irresistible about seeing people behaving badly.

RG: The effect of the internet today is to create what they call echo chambers of ideas, meaning our searches are only going to reaffirm what we previously searched. Search engines cater to our tastes, so we’re not going to get the opposite ideas.

But in 1968, there were only three networks, so everyone watched the debates. So I think Vidal and Buckley hoped they could change people’s minds. But people who go on Fox or MSNBC now know the types of people who watch those networks.

SY: The film mentions how Vidal was upset that no one truly remembered him at the end of his life. Do you feel that was interesting aspect of his feelings, since he was known for being so shocking for most of his career?

MN: I think they both had that feeling, as they were both huge figures in our culture, but then outlived their moment. I think there’s always something sad about that in a person’s life. But that, to me, is also the most human part of it, as it happens to so many of us. At a certain point, older people aren’t in the center of culture anymore, which is something that we connected to.

RG: There is also always someone new who’s coming in to attack the institutions, and who replace the current commentators. That’s what happened to Vidal and Buckley. In 1968, Buckley was drawing people to the Republican Party, and then he became the epicenter of it in 1980 with Ronald Reagan. But by the time George W. Bush became president, he was hardly known.

SY: ‘Best of Enemies’ has played in several film festivals, including having its world premiere at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, before playing at SXSW and the AFI Docs Film Festival last month in Washington, D.C. What was your experience of bringing the movie to the festivals, and how did audiences respond to it?

MN: It was a great experience, because you never know what people are going to think…

RG …because we made the film in a small room with very few people.

MN: But from the first screening on, the fact that we saw it as a cautionary tale and an absurdest comedy, it played as both, which was rewarding. It’s been great to see people get as excited about as we have been.

RG: I still get chills thinking about the laughter the film received at our very first screening, and how rewarding that was. It’s a serious film, but it’s also very funny, and that first audience affirmed it for us.

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

Written by: Karen Benardello