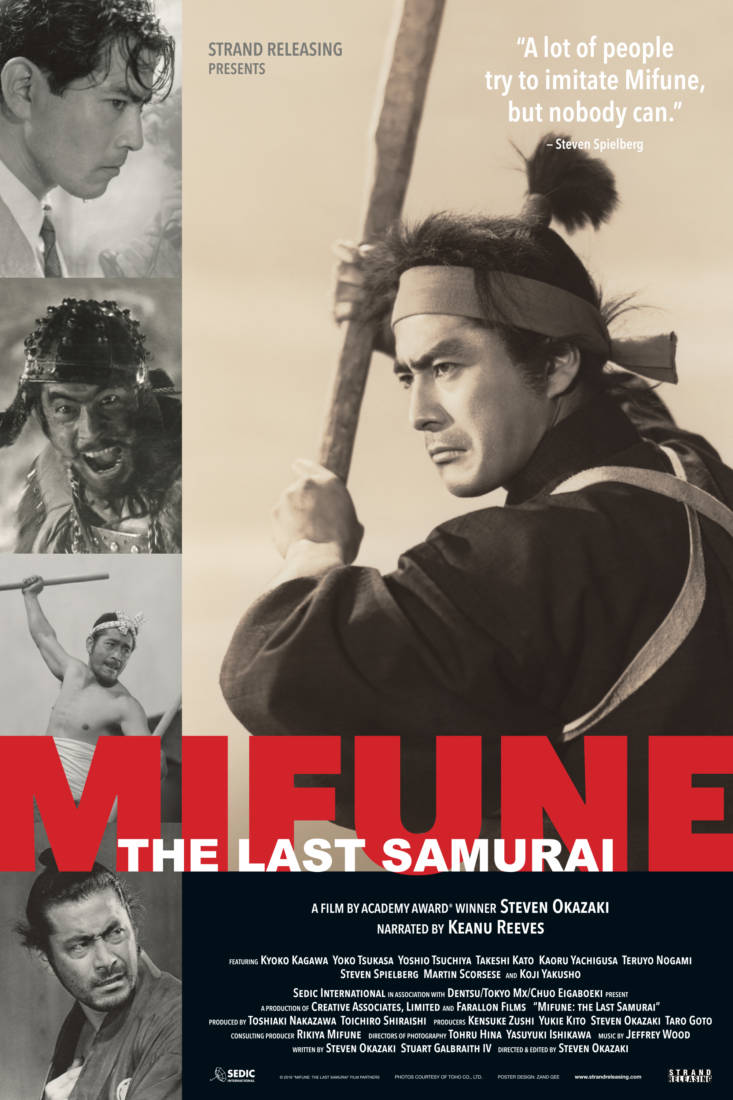

Being a revolutionary pioneer in a particular field of work should be an accomplishment that’s continuously celebrated. Unfortunately, not all visionaries receive the praise they deserve for launching an honored way of life into mainstream society. That’s regrettably the case with actor Toshiro Mifune, who began to garner fame in the late 1940s after he served in World War II. In Oscar-winning filmmaker Steven Okazaki’s new documentary, ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai,’ the performer is highlighted as not only being the first international Asian, but overall nonwhite, star who garnered worldwide attention in the action genre.

While Mifune’s work has left lasting impressions on dedication genre fans, the majority of the world has largely forgotten his films. Okazaki hopes his film will remind people of the actor’s influence, not just on the genre in which he began working in over half a century ago, but also on all modern cinema.

The influential documentary, which was an official selection of such film festivals as the Telluride Film Festival 2016, the AFI Film Festival, the BFI London Film Festival and the Hawaii International Film Festival, began its theatrical release this past weekend at the IFC Center in New York City. ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai’s distributor, Strand Releasing, will expand its theatrical run into such cities as Beverly Hills, San Francisco, Denver, New Orleans, Santa Fe, Seattle and San Diego over the next couple of months.

Narrated by Keanu Reeves, the documentary was directed by Okazaki, who also co-wrote it with Stuart Galbraith IV. The helmer also served as a producer and the editor on the film.

‘Mifune: The Last Samurai’ explores the evolution of the title samurai film star, including Mifune’s childhood and World War II experience; his accidental entry into a career in movies; and his dynamic but sometimes turbulent collaboration with his frequent collaborator, director Akira Kurosawa. The two filmmakers made 16 movies together, including ‘Rashomon,’ ‘Seven Samurai’ and ‘Yojimbo.’ Together, the actor and director shook the film world, and inspired such diverse film as ‘The Magnificent Seven,’ Clint Eastwood’s breakthrough movie, ‘A Fistful of Dollars,’ and ‘Star Wars.’

During a recent interview over the phone, Okazaki generously took the time to talk about co-writing, directing, producing and editing ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai.’ Among other things, the filmmaker discussed how he was interested in making the documentary, as he wanted to remind audiences how powerful the actor’s films have had not just on Japanese cinema, but movies worldwide. The director also shared that once he signed on to make the documentary, he decided to interview filmmakers who have been influenced by the actor, including Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, as well as several of Mifune’s surviving collaborators, family members and friends.

Okazaki initially spoke about what inspired him to direct a documentary about Mifune’s movie career, and how his films have influenced other films in the action genre. “What interested me in making this movie was to be able to remind people how powerful his films were. I think this moment in time, we have forgotten the great movies not just in Japan, but also in world cinema,” the filmmaker explained.

“With all the new media that’s available, such as Netflix, people have embraced this appetite for great films. But they’re still ultimately missing all of this great cinema,” Okazaki continued.

“Even great American directors and actors like James Stewart, John Ford and Wayne have become forgotten names. Likewise in Japan, filmmakers like Mifune and Kurosawa have even become forgotten,” the documentary’s helmer also revealed.

“But these types of films are so much fun, and they have have been so hugely influential. I don’t think people realize that American cinema would be very different without Kurosawa and Mifune,” Okazaki pointed out. “We wouldn’t have ‘Star Wars’ and all of the great films by Clint Eastwood.”

“I just thought this would be a fun film to do. I was talking to a producer in Tokyo about doing a film on the history of the samurai. I thought that would be a fun break from the documentaries that I usually do, which focus on life and death,” the director also revealed. “Since I usually run around on location, I thought this would be a nice, comfortable thing to do. I could watch movies and talk to people about it.”

But when Okazaki started looking into the possibility of making a documentary on the history of samurai films, the producer he started speaking with pointed out that that type of project would be difficult to make. The producer explained that the director “would have to work with different Japanese studios, and they don’t really work together. They’re all very possessive of their own films.

“But he told me there was another producer in Tokyo, who’s one of the top producers in Japan,” who might be interested in making a documentary about Mifuene. The producer “made ’13 Assassins,’ which was a big hit in Japan, and is also available on Netflix. He also made ‘Departures,’ which is a really nice film. It won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film (in 2009).”

The producer, Toshiaki Nakazawa, worked his way up through Mifune Productions “as a young man, so he felt a debt to Mifune and his family. So he wanted one of his last films to be a documentary on Mifune,” Okazaki divulged.

“So I volunteered, and told him not to look for anybody else. I thought we could reach more international audiences” if they collaborated together on the documentary. So Nakazawa “said yes, so we went off and running,” the director added.

Once Okazaki signed on to helm ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai,’ he had to start doing practical research into the actor’s life, in order to determine how he wanted to tell his story on screen. “I had to figure out who was still alive. The actors, directors, cameramen and set designers Mifune knew came up through World War II. They then restarted the Japanese film industry after the war, during the 1950s and ’60s. But a lot of them are gone now.”

So Okazaki and his crew started scanning “the credits of all the films we were interested in, just to see who was still around. For some of the movies, it was pretty scant. Often times, we would find out that someone had just passed away, or not in shape to do an interview. So it was a process to figure out who could be in the film. But luckily we got some great people, and they were excited to talk about the good old days, and their relationships with Mifune.”

During his research process, Okazaki had to go through a lot of material. He added that he was interested in showing highlights from the early films in the samurai genre. “But unfortunately, there aren’t many silent samurai films left. A great percentage of them were lost or destroyed during World War II. Often times, the films would be shipped out, but then they would be too costly to ship back. So films are still turning up now in places you wouldn’t expect, like Belgium.

“With the later films, it’s quite the opposite. After this great era of filmmaking, Mifune made a lot of mediocre films in the ’70s and ’80s. But it was still a fascinating process to go through them all,” the director revealed.

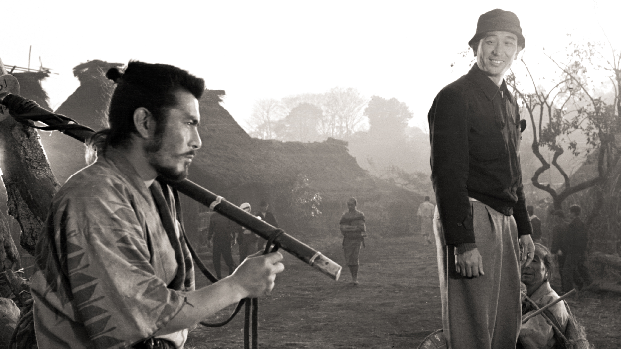

The director added that Mifune and Kurosawa’s families, were very involved in the documentary. “They had a lot of archives, including a lot of photos. Some of them weren’t organized, so we had to figure out what movie they were from, and who was in the photos. Some people were very obvious, such as Steven Spielberg.”

Further speaking of how ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai’ features filmmakers who have been influenced by the actor, as well as several of his surviving collaborators and family members, Okazaki shared his experience of conducting the interviews. “I wanted to make people feel as comfortable as possible, and let them tell the stories they wanted to tell. Japanese people are pretty private.

For instance, in the documentary, “you can see one of the actresses, Yôko Tsukasa, talk about how bad the food was on location. But she was so polite; she said, ‘It wasn’t the greatest food,'” the director shared.

“But the Japanese don’t like to brag or be overly critical. So you really have to work with that, and find ways to bring them out. But they have the stories in them, and you just try to get them to tell you everything they can,” Okazaki added. “I think making people comfortable is the key to interviewing them.”

The director added that he had written down approximately 20 to 30 questions for each person he interviewed for ‘Mifune: The last Samurai.’ But he just used those questions as a starting point for the interviews.

Once he finished conducting the interviews, and secured the clips from Mifune’s films, Okazaki began working on the editing process for the documentary. “Like with every film, you want to keep things moving, and try not to be repetitive. I don’t like to over make a point; I think it’s better to keep the story going along. Then hopefully, the end result will be compelling,” the filmmaker mentioned.

“We used a lot of stills, but we were restricted to a degree because of the economics. We also could only use a small number of clips from his films,” Okazaki revealed. “It was a challenge to just use a lot of stills, and use the clips well; we couldn’t just let them run. With some, we just let the scenes evolve, and with others, we would play them for even half a second. But I think that gave the film a nice rhythm.”

The helmer added that he knew he wanted to include a sequence about the development of the samurai genre since the silent era. “I wanted to look at that character of the samurai, which is the opposite of the Japanese society. In Japanese society, you’re supposed to fit in, but the samurai is very individualistic. He stands up for what he believes. I thought it was important to establish that, so we made that a part of the film.

“In order to understand Mifune, you really have to understand a bit of his childhood, and what it was like for him growing up in Manchuria, away from Japanese society. You also have to understand his experiences during World War II, when he had to watch other young men die during kamikaze raids,” Okazaki noted. “Both of those things had a profound and lasting effect on him. His friends that he later went drinking with noted that those subjects came up often with him.”

Mifune’s life has not only left an impact on his family and friends, but also on movie audiences, particularly those who saw the documentary on the film festival circuit. Showing the movie at the festivals “has been very emotional. We first had a screening for the film’s participants and crew, as well as the Mifune family. The people who knew Mifune cried at the screenings, but they were also very happy. So the private screenings were very nice.”

The director added that ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai’ has played at about 15 festivals. “I didn’t attend them all, but I did realize what an avid fanbase there is for Mifune all around the world, especially in American college towns and big cities…We just showed it in Los Angeles, and the audience was pretty diverse.

“Shockingly, there hasn’t been anything like this before,” Okazaki noted. He also pointed out that it’s been more than 50 years since Mifune’s collaboration with Kurosawa ended, “so this film was long overdue. It’s a sense of relief that people may go back to his movies…I think this film will remind people to watch Mifune’s work again.”

The director added that he feels it’s his job to help the actor’s work be seen by today’s audiences, and “make people remember the names Mifune and Kurosawa in world cinema again. I know they’ll think his films are interesting when they see him.”

Since Mifune was not only the first international Asian, but overall nonwhite, action star, Okazaki feels the actor’s legacy has influenced the genre, from when his movies were first released until now. “I think his influence, whether or not people realize it consciously, has been huge. The concept of the loner hero is still prevalent today. I hope the film reminds people of that.”

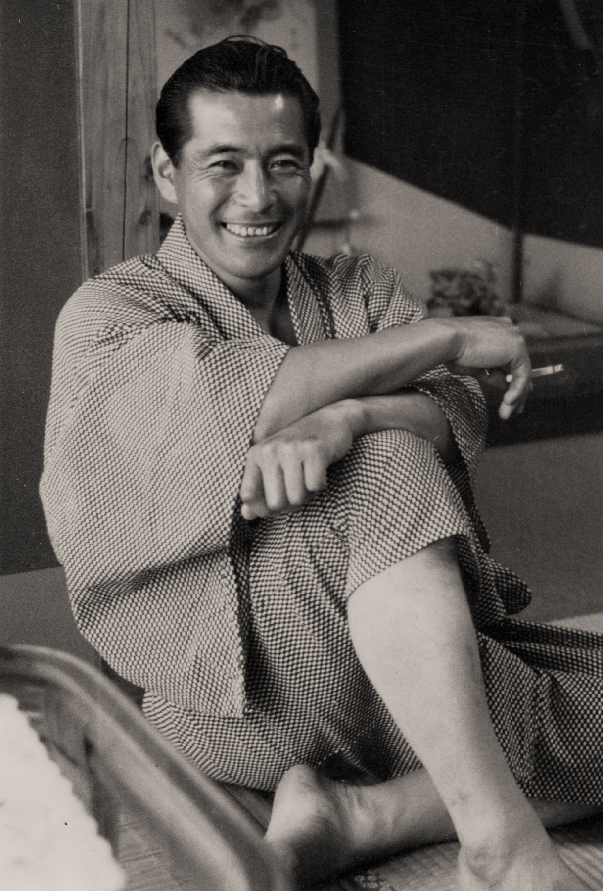

Watch the official trailer for, and check out the poster from, ‘Mifune: The Last Samurai,’ and view stills of the actor, below.

Written by: Karen Benardello