NISE: THE HEART OF MADNESS (O Coracão da Loucara)

Outsider Films/ Strand Releasing

Reviewed by: Harvey Karten, Shockya

Grade: A-

Director: Roberto Berliner

Written by: Flávia Castro, Mauricio Lissovski

Cast: Gloria Pires, Filipe Rocha, Claudio Jaborandy, Simone Mazzer, Roney Villela, Fabricio Boliveira, Charles Fricks

Screened at: Review 2, NYC, 4/17/17

Opens: April 28, 2017

Aside from Lizzie Borden, Ilsa Koch and Nurse Ratched, men are more violent than women. Couldn’t you predict that the infernal male gender would fall prey to its genetic coding and brutalize psychiatric patients? Don’t think that driving ice picks below patients’ eyelids into the brain to cure schizophrenia was a technique approved only by families of limited money and education. Joseph Kennedy, father of the great president and of a daughter, Rosemary Kennedy—who embarrassed her lofty family by tempestuous mood swings—approved her treatment of prefrontal lobotomy which the Kennedys believed would calm her. According to Clyde Haberman in the New York Times of 4/17/17, in 1941 at age 23, Rosemary underwent the barbarous treatment also known as psychosurgery. There were side effects; she had to stay institutionalized, and spent the remainder of her life unable to speak clearly or walk without a limp.

Back to that infernal, violent gender: men. As illustrated with great interest by director Roberto Berliner in a script composed by Flávia Castro and Mauricio Lissovski, Dr. Nise da Silveira, who became one of Brazil’s most celebrated psychiatrists, had to push quite a few men aside in order to accomplish good deeds in a psychiatric hospital on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro (the film is in Portuguese but burdened with English subtitles that are white and blend into the picture to make them difficult to read). Berliner, who had a hand as a director of documentaries, this time wisely avoids that approach in this fleshed-out narrative drama. He focuses primarily on Gloria Pires in the title role, a woman who before getting a job in the hospital, was both jailed for suspected of being a Marxist and as a student in medical school, the only female in a class of 157. The fur was flying in the 1940s almost as soon as she entered the decrepit and filthy institution, ordering a nurse Lima (Augusto Madeira) to clean up (he refused) but gaining the support of nurse Ivona (Roberta Rodrigues).

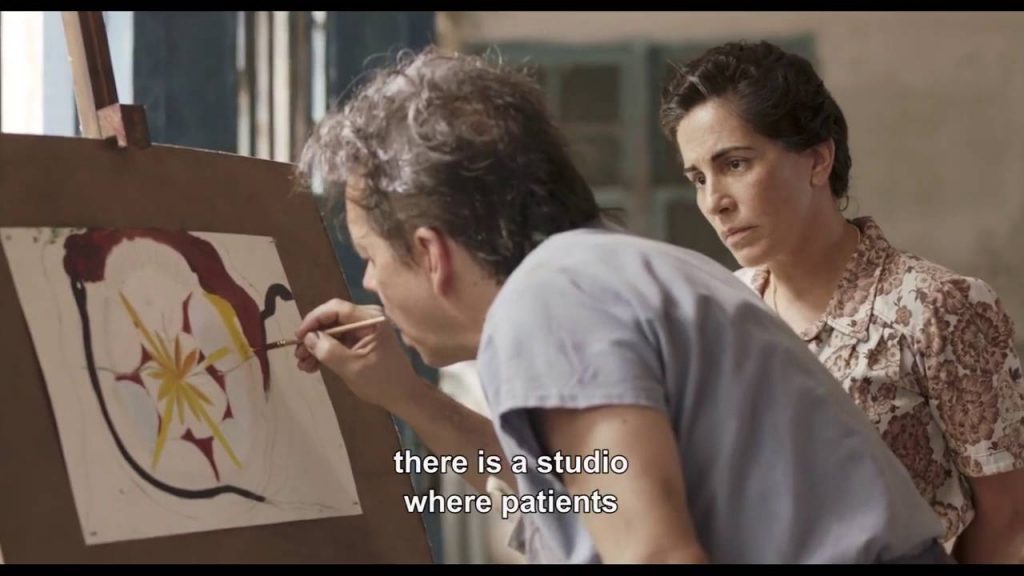

That done, she goes to work upsetting most of the male staff, insisting on calling the patients “clients” instead of the accepted term “nutcases.” But that does not change the fortunes of the clients, not yet, as their responses range from catatonic to physically aggressive. An acolyte of the psychologist Carl Jung, she believes that the clients, like the rest of us, indulge in behavior often governed by their unconscious, and what better way to make use of that aspect of the brain than by encouraging them to paint? It took time, but paint they do, and what emerges from the canvases is a spectacular array of what we call modern art, vivid illustrations of what is going on deep in their medullas. She couples paint class with a trip outdoors to a park, where the sunlight appears to melt away their troubles at least for a while. She encourages them to return to oils and canvas and to continue their affection to a group of mongrel dogs to the disgust of Dr. Cesar (Michel Bercovitch), who is not fond of the ticks and stools left behind.

Ultimately their work gets displayed at an exhibition in Rio, soon making the rounds of halls of modern art, all organized by a well-known art critic, who upon visiting the hospital has been amazed by the quality of the work. In fact, what is amazing to me and probably to many of the people who will attend and enjoy the authentic performances of the ensemble (yes, we may well wonder whether Berliner hired actual schizophrenics for the movie) is: how does it happen that a number of these people, who never took an art lesson before their commitment, could be so professional with brush and paint? In fact the whole story could unfortunately lend credence to the thought that renowned modern art could have been a product of their own five-year-olds, mentally ill or otherwise.

Andre Horta’s camerawork gives the narrative drama the look of a professional documentary without any of the boredom that talking heads evoke. At the same time his lenses capture the authenticity of the proceedings as though he were actually filming in a psychiatric hospital. The real Nise da Silveira died in 1999 at the age of 94, but not before she appeared in an epilogue, looking every bit her age, jokingly calling the cameraperson a nutcase. A nise film.

Unrated R. 106 minutes. © Harvey Karten, Member, New York Film Critics Online

Comments, readers? Agree? Disagree? Why?

Story – A-

Acting – A-

Technical – A-

Overall – A-