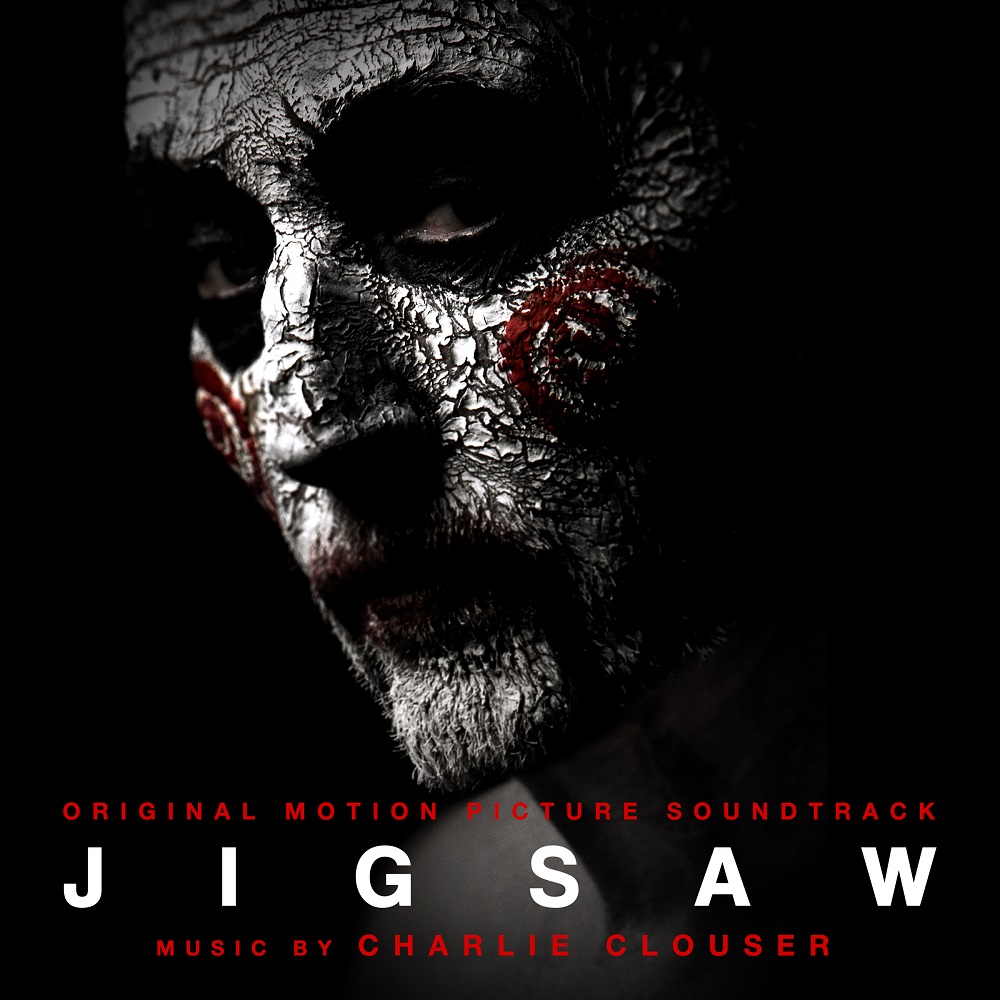

With eight Saw films now under his belt, composer Charlie Clouser is no stranger to the torturous tale that fans have grown to love. Clouser, once a member of the band Nine Inch Nails, has become an integral part of the franchise with his famous “Hello Zepp” theme appearing in all the films and being played more than ten million times on Youtube alone. With Jigsaw currently still holding number five on the box office charts after several weeks in theaters and Clouser surprising fans with the announcement that Lakeshore Records would be releasing two Anthologies of his Saw music encompassing all eight films on both CD and vinyl, the franchise continues to prove it is here to stay and future films are not out of the question. We decided to speak with Clouser more in depth about his work on the films, read here.

A lot of critics are saying Jigsaw is a reinvention of the franchise and paves the way for future installments. Is there something you would like to try, musically, that you haven’t yet if there were to be more films?

I agree that Jigsaw is a bit of a fresh take on the franchise. It has a brighter and sharper look and feel than some of the dark and murky earlier chapters, and if the franchise continues I’d like to bring more energetic “espionage / thriller” elements into the score, as opposed to the total darkness of most of the franchise. I had the opportunity to do a little bit of this in Jigsaw, since part of the story line takes place in the outside world as opposed to being entirely in grungy dungeons like some of the previous films, and moving forward I think that would be a good approach to take. This might help to widen the appeal beyond the hardcore SAW fan base, and musically would allow for some pretty dramatic contrast between the ambient, underwater feel, and a more pulsating, tense, thriller aspect to the other side of the story. That approach seemed to work well in the few spots I was able to try it in Jigsaw, and seems to make the trap scenes hit all that much harder when you’ve just come out of a scene that has music with a less insane feel.

Jigsaw is the 8th movie in the franchise. How do you keep your score new and fresh?

Before I begin the actual writing process for each of the sequels, I always take a week or two to record a new batch of sounds that I think will fit. I generally try to get the skeletons of a few important cues mapped out in terms of the key and tempo, and then I just woodshed for a while in the studio, experimenting with processing guitars and synthesizers, recording some new percussion, and messing about with torturing a piano or some of my bowed metal instruments. This gives me a stockpile of new sounds that I haven’t heard or used before, and if I get back into the writing phase before the excitement of all those new sounds wears off, it usually inspires some new directions that I wouldn’t have thought of if I was just staring at the same collection of sounds that I’ve used before. If I need to reinterpret some melodic themes from past sequels, having a new batch of sounds on which to play them keeps things sounding different from sequel to sequel. I really enjoy the process of musical sound design, and I’m very much the type of person who reacts and responds to interesting new musical sounds, so this approach satisfies my urge to just stay up all night in the studio making weird noises, and at the same time gives me a fresh batch of one-off sounds that will be unique to each project.

What did you do differently, musically, in Jigsaw that you haven’t done in the others?

Since there’s a big chunk of the storyline in Jigsaw that takes place in the outside world, I tried to have the score in those scenes sound a little less murky and indistinct, with more bright and pointed sounds and less dissonant chord progressions. So much of the musical landscape of previous Saw sequels has had a dark, almost underwater feel, which seems appropriate when the action is taking place in rusty underground traps and dungeons, but when we go out into daylight that just feels a little out of place. For Jigsaw I used some phrases and progressions on strings that sound more “normal” in these outdoor scenes, and for some of the scenes where the characters are uncovering evidence and interrogating each other I took the kind of approach that I would for a more conventional thriller or espionage type of project, with subtle pulsing synth parts and less “full on” sounds. I think this helped to give the score kind of a split personality, with these “outside world” segments contrasting against the traditional dirge-like familiar sound of Saw more dramatically at the start of the film, and the two approaches gradually converging as the film went on and the characters are inevitably sucked down into the dark atmosphere as they enter the barn towards the end of the picture. For the trap scenes I also took a slightly different approach than before, using brighter sounds and more legible synthesizer parts that I usually use, and this was a reaction to the Spierig brother’s visual style, which is sharper and less cloudy than some of the previous director’s approaches. I wanted the trap scenes to have a bolder, more energetic feel than earlier films, so I used a more stripped-down set of sounds and arrangements which let me build trap sequences that will hopefully feel more frantic and a little more high-tech than before, while still having those industrial music influences that have always been a big part of the Saw sonic landscape. The players’ deaths in Jigsaw are more real and shown with more details and effects that no other SAW movie has yet to achieve. Because it is taken to another level does that mean that your score has to also, or does that mean your job gets a little easier? That added level of detail and legibility that the Spierigs brought to this installment definitely influenced how I approached the death and trap scenes, but I wouldn’t say it made my job easier! I did want to have the score feel a little more like the lights were on as opposed to having everything shrouded in darkness, and for me that means using sounds with more prickly high frequencies and sharper, more pointy sounds and less of that “drenched in dark reverb” sound than in earlier films. I shifted a little bit away from building the score from the sounds of rusty, clanking metal and more toward precise, high-tech synth sounds. While this wasn’t a complete and total re think of how the score sounds, it was more about letting that new family of sounds share the stage with those familiar metallic and industrial elements in equal measure. I didn’t want to totally re-invent the wheel, but maybe just put fresh tires on it, if that makes sense.

The first SAW is now over a decade old. How to you think you have changed as a composer from then

to now?

I’ve learned so much in the years since the first Saw, which was the first feature film that I was completely in the driver’s seat for, and my experiences doing other films and television series has just given me more options in terms of the tools and techniques I have at my disposal to be used to solve a musical puzzle. In my mind there’s a very clear set of chord progressions and melodic approaches that are appropriate to use in a Saw film and I generally don’t use these approaches on other projects. Saw has sort of taken on a life of its own and sometimes I think of it almost as though each movie, franchise, or television series is like a different band; and I’m like a session player that records or tours with a bunch of different bands, altering my approach to fit each situation. A good metaphor would be the guitarist Robin Finck – he wouldn’t play a bluesy, Guns-N- Roses style guitar solo over a Nine Inch Nails song, even though he can absolutely kill it when he does play that style. I try to keep that line of thinking in the back of my head, and let my musical style be dictated by the visual style of each individual project. This sort of ground rule helps to narrow down the range of musical styles and sounds that are fair game for whatever project I’m working on, and helps to give each film its own sonic footprint. Even though my toolbox is much bigger now than it was when I started, I still try to keep in mind the simple, targeted approach that I took years ago when the range of tools at my disposal was somewhat smaller, in the hopes that my results will stay tightly focused and on target.

When you were working on the original SAW was the initial direction what ended up in the film, the Hello Zepp theme for example, or did you want there to be another tone?

For the original Saw film, I’d say that the finished score really was very close to what I set out to do, and there really wasn’t a lot of fishing around or looking for the right tone or approach. For years I had been collecting sounds and techniques that I loved but hadn’t yet found the right project to use them on, so when I began work on Saw it felt like I had a drawer full of sharp knives and I finally had the right opportunity to whip ‘em out. I did have a game plan going in, which was that the whole score should sound murky and indistinct, all the way up until the end reveal montage begins and Hello Zepp kicks in. At that point in the film, I wanted the score to make it feel like the lights had been switched on and were shining in the audience’s face. That’s why I used the small, tight-sounding string quartet and the simple, bold musical phrases in Hello Zepp, as opposed to the distant, cloudy sounds and drifting, wandering chord progressions that I used in the rest of the score. Fortunately, having this game plan in place before I began writing worked well and provided that tonal shift and a bit of a kick into high gear at the end of the film, and helped to make that end reveal montage stand out in the audience’s mind.

What is your best memory of working on the SAW films?

Over the years the Saw franchise has given me some great opportunities to work with some musicians whose work I’ve admired, and having Wes Borland come in to play guitar on my score for Saw II was a treat. Wes has such a unique style and seems to be a bottomless pit of weird and cool ideas. I just had to make sure I was ready to record right from the get-go, because as soon as he heard the track he was going to play over the ideas started flowing and he came up with unexpected and inspirational sounds and riffs immediately. Another highlight was meeting and working with Chas Smith, an experimental musician and instrument builder whose work is truly unique and a perfect match for the sonic landscape of film music. His immense, hand-built metal creations are half sculpture, half musical instrument, and all awesome. I was able to record some of the dread-inducing tones that his instruments can create, and these ominous sounds have formed an important part of the sonic footprint of my scores. Discovering new collaborators who operate a bit outside the normal orbit of film music always gets my creativity flowing, and these two guys are definitely orbiting at higher altitudes! When we were working on the first Saw film, we knew we had something special on our hands, but you never really know if something like this will find its audience until it’s out in the world, so it was a big thrill to see that it was going to open at the big room at the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Seeing the logo plastered across the double billboards in front of the Chinese was a big thrill, and I’ll admit that I did take a selfie in front of the theater just in case that was my only chance to “play the big room”. As it turned out, over the next few years I’d have more than a couple of films that opened in “the big room”, so my fears were unfounded, but the thrill of seeing my work in a legendary theater for the first time was a once-in- a-lifetime moment for sure.