Netflix’s High Flying Bird is a basketball film, only it isn’t. It’s actually a social commentary on power, wealth, and race — all amid the backdrop of basketball. It explores the undercurrents within the professional game, specifically the sometimes tenuous relationships between predominantly black basketball players and their nearly white billionaire owners — a dynamic described by The New York Times as capitalism in sports. It is to borrow from the Times, a “feisty, twisty fable of labor and capital in the 21st century.”

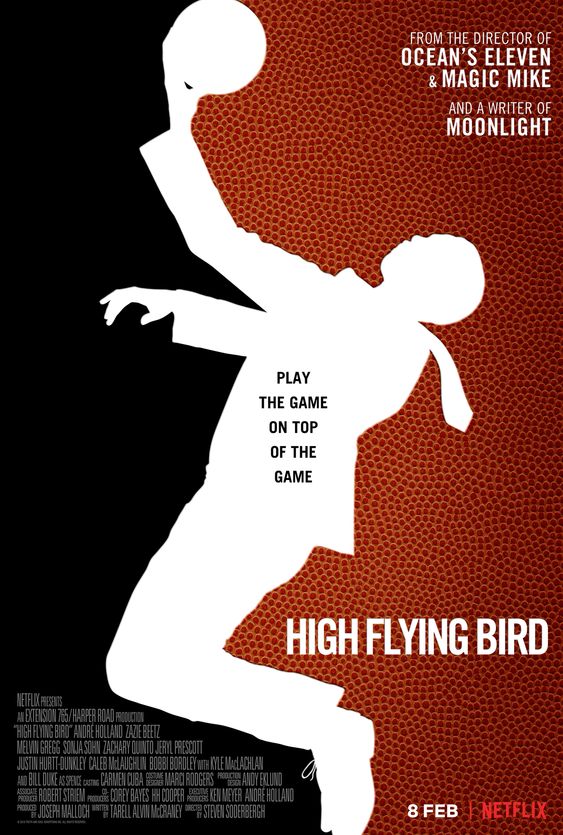

High Flying Bird is a slam dunk of a film, one that draws plenty of parallels with the real game itself, which in this case is the NBA. The most obvious of these parallels is the lockout, the prism from which Steven Soderbergh (who also helmed Unsane) explores the details of life in the big leagues. Four times the NBA has had a lockout, which in its simplest form is an owner-imposed work stoppage. The lockout in High Flying Bird reaches a stalemate, mirroring what happened in the 1998–1999 and 2011 NBA lockouts. Soderbergh’s lockout ends thanks to the machinations of agent Ray Burke (played with aplomb by André Holland, who was part of the Shock Ya!-approved Moonlight). The real-life lockouts, on the other hand, necessitated plenty of negotiations amongst owners, agents, and players before they were settled.

Additionally, High Flying Bird’s very first scene — Burke haranguing top pick Erik Scott for taking out a massive loan to sustain an extravagant lifestyle — shows the dangers of being a young, black athlete suddenly pushed into the spotlight. Scott’s is a cautionary tale of wanting too much too soon, one that mirrors a reality common among today’s basketball players. Burke, though, is not spared from the politics of the big league, as his boss (played by Zachary Quinto, producer of The Banshee Chapter) holds his corporate card hostage. Burke is placed in a virtual no-win situation: find a way to stop the lockout or get fired. Yes, even the suits involved in the NBA face mounting pressure both from the players they represent and the firm they work for.

Lastly, High Flying Bird artfully recreates the tensions that forever envelop player-owner relations. Soderbergh suggests in the film that despite earning millions, NBA players are nonetheless merely workers, and are at the mercy of their billionaire owners. The fact that there are racial underpinnings to this dynamic exacerbate the situation to a near untenable degree, and this is made apparent in High Flying Bird. There are so many layers to these relations that they tend to be combustible, especially since livelihoods are at stake.

The real-life NBA saw this exact situation play out in 2014 when then Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling made racially charged comments along the lines of avoiding interaction with black athletes. Players were predictably outraged, leading to silent protests and threats to boycott games. The NBA eventually intervened, fined Sterling, and nudged him to sell the team. The Clippers were eventually sold to former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer. This episode could have sent the team into a tailspin, but it didn’t; instead, the Clippers recovered remarkably and have become one of the NBA’s most well-run franchises. Even in a state of flux this season they have remained competitive, despite bwin Sports NBA giving them very long odds of winning the title. But given the aforementioned Sterling controversy, the Clippers deserve plenty of credit for closing ranks rather than unraveling.

Similarly, High Flying Bird deserves just as much credit for depicting the behind-the-scenes business deals that happen in the world’s best and biggest professional league. The fact that these nuances are masterfully tackled in the film is what makes this Netflix offering a must watch.