One of the most popular digital music distributors musicians use to get on Spotify, iTunes and Amazon, may not be the good deal it seems to be when you take a deep look

“Whether DK charges hidden fees depends on what you consider ‘hidden.’ – Billboard. It’s a weird and competitive world in digital music distribution, and it can be very hard to tell what’s going on before an artist has already invested with one service or another.

What exactly is a Hidden Fee?

DistroKid isn’t a dishonest company. DK’s constantly online answering questions in forums and getting services talked up in blog posts like this one.

The root of the matter is in deciding just what, exactly, is a hidden fee?

The trick is that artists can’t point to a distribution package and have it be suitable for every other artist. The way many distro companies get around this is by starting with a certain, minimal amount and offering a minimum of services with this amount. After that, artists start paying ( often a lot) more.

Is that “hidden?” In any case, distribution costs more for many artists than they expect at the outset. Let’s look at DistroKid, one of the most popular options, just as an example of how this can shake out.

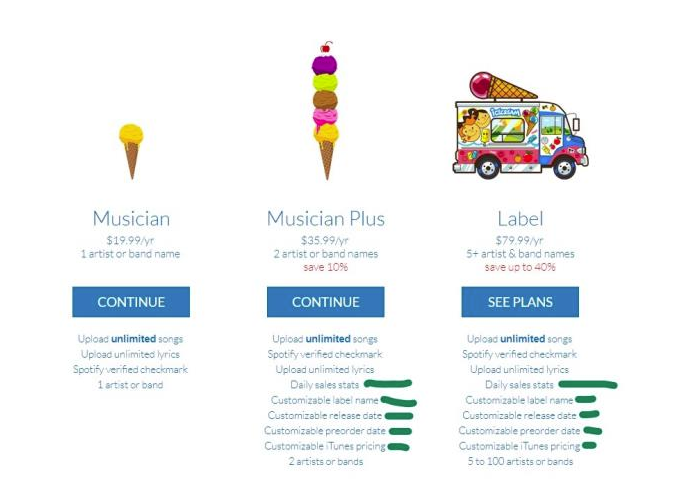

Unless you’re publishing lots of bands, the 40% savings won’t apply.

You Get What You Pay For

DistroKid’s minimal distribution package comes with very little. 19.99 USD per year for one artist buys distribution for that year, a UPC code, a Spotify check-mark verification, and the option to upload lyrics.

Daily sales stats aren’t included, either. In fact, artists wanting control over the date of their release, the name of their music label, any preorder or presale dates, or daily sales statistics will need to forfeit 35.99 USD each year for the “Musician Plus” package.

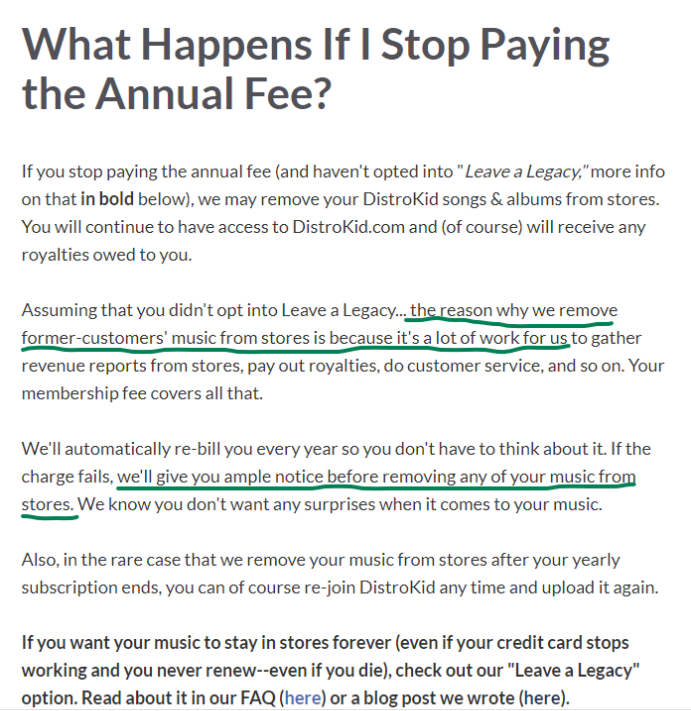

The deal-breaker for lots of artists will be the annual payment. If you don’t pay after 12 months, your distributed music comes down. If you want a single or album distributed for 13 months, it’ll cost you 39.98, not 19.99. And 11 months later you’ll be paying for distribution of those songs again.

Of course, a year isn’t much time for music to gather a following. It’s hard to imagine an artist only wanting music available for streaming or purchase online for just a year. Maybe it’s a limited-time-only album such as a few pop stars like to do sometimes. Even those tracks wind up on a compilation record sooner or later, though.

Not to mention, it takes a very long time to build a fanbase, much more than a year. If you’re trying to make a music career happen, one year is not what you’re going to pay for in terms of distribution. If you were to have an album distributed for only three years, for instance, that’s going to run 59.97 USD, not 19.99. Then the music gets removed from stores, anyhow.

While that’s going to be most important for many artists, though, it’s far from the only consideration.

It’s only optional if it’s not extra.

What Do You Consider Extra?

Let’s assume you don’t mind the yearly subscription. There are other services which don’t come with the minimum package, either.

The least-expensive model excludes the ability to choose what fans pay at iTunes, for example. One of the biggest ways artists can interact with their audience is in controlling the price of their music. Bring the price down, more people pay. Move it up and you’ll make more per release, but sell less of them. This is the most basic thing any seller of anything can control, outside of just not selling anything at all.

Want to say how much your music costs at iTunes? That’s $35.99, not $19.99.

All the above is before you’ve actually chosen a package. After that it gets more detailed.

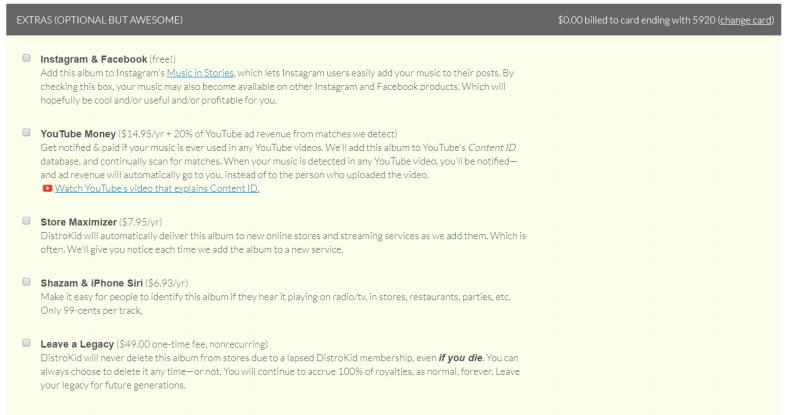

DistroKid offers a “Store Maximizer,” “YouTube Money” and a service which splits royalties.

These are all called extras, but some won’t seem extra to every artist.

“Store Maximizer” costs 7.95 USD, annually again. The artist pays this every year. With Store Maximizer, DistroKid will add artists’ distributed music to stores which are added to their distribution network. This apparently happens “often.”

Artists who want their music available over DistroKid’s whole network need to pay at least 27.94 (not 19.99) every year. Stores occasionally stop selling music or go out of business, probably, but DK doesn’t say if artists who pay for Store Maximizer are told when this happens. You just get the comfort of knowing your music is being added to stores, also.

Many artists won’t consider “YouTube Money” extra, either. Besides that original 19.99, DistroKid wants 14.95 USD per year to ferret out uses of your songs on YouTube. DK collects ad revenue from those uses for the artist, minus 20% of that revenue. DK takes that percentage in addition to the 14.95 annual fee for YouTube Money alone.

Of course, an artist doesn’t need DistroKid to file complaints with YouTube about unfair usage of their music. But how can artists find those unfair uses? They can’t. As YouTube points out, their ContentID system is only available to their music partners. That means DistroKid in this case. Artists can’t register art with YouTube ContentID. So if you want to be paid when somebody uses your music on YouTube, either you accidentally stumble on it (not going to happen) or you pay.

Note that YouTube Money costs about 75% more than you might have expected to pay for your package when you started.

When you distribute your music, you’re probably going to want to be paid for it.

Royalty Payments to Everyone Are Extra

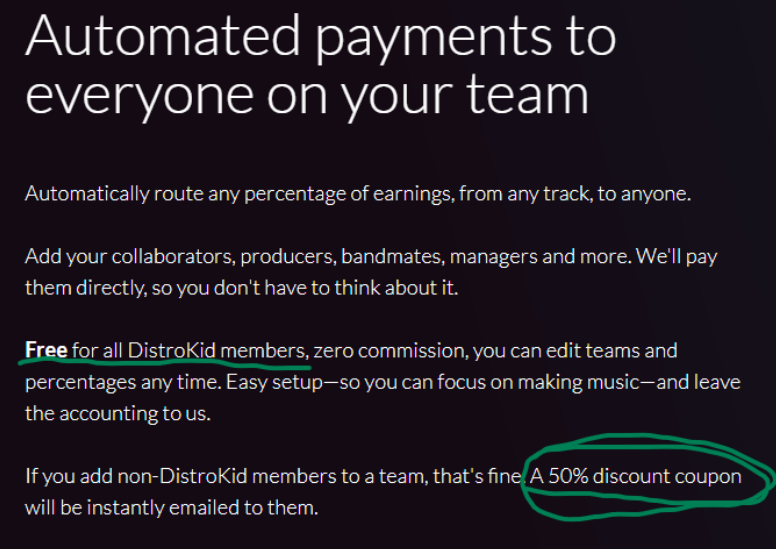

If an artist were part of a five-piece band distributing an album, DistroKid would split royalties for everyone and pay directly. That’s super useful if you’re a studio group of collaborators from all over the world. Nobody wants to need to trust someone to split up the money.

DistroKid needs payment info for each member, of course. And maybe it’s going to cost an annual fee to pay everyone. But for this particular service, DK requires each band member to have their own subscription.

The upshot of this is that groups who need to split royalties will need an annual subscription for each member. Right now, DistroKid supplies a 50%-off coupon soften the blow, but that discounted rate almost certainly can’t be counted on every year afterward. So, a five-piece crew dropping an album will pay about 60 USD for the year so everyone can be paid their share and then 100 altogether to keep it distributed after that, apparently.

But the most obvious extra lots of artists won’t consider so extra is DK’s Legacy package.

50% off is still 50% more for this year. But it’s probably not 50% off next year.

At a One-Time Cost of Much More, Your Music Stays Online

In the case of DistroKid, the annual subscription is what most artists will balk at.. Nobody likes the annual subscription. You can’t say DK is hiding this fee — they’re not. But for the artist, it doesn’t cost 19.99 to distribute, either, unless they don’t want it distributed for very long.

So the actual cost of distribution is somewhere in-between, and DK has a solution for this. They call this their “Leave a Legacy” package. For a one-time fee of 49 USD — approx. 250% of the original asking price of 19.99 — DistroKid won’t remove distributed music from stores if annual payments stop. This means that to permanently distribute an album via DistroKid costs a total of 68.99 USD, not 19.99.

Also very important is that, while a minimal DistroKid subscription comes with unlimited music uploads for a single artist, the Legacy service must be paid for each release. Artists who don’t want their distributed music removed from stores will probably want to pay at the album price, too. Leave a Legacy costs about 30 USD for each single (in addition to the original subscription price) so albums are much less expensive to distribute.

You can’t expect something for nothing, but you definitely pay for everything you get.

Hidden Fees, or Extra Fees?

Hidden, extra — whatever. The point is not that distribution services purposefully hide the cost of their services from their customers. That would make no sense. Customers need to know what they’re going to pay before they even know if they can.

The point is that artists decide what they want in a distribution package, and that’s what distribution means to them. Anything outside that definition is extra. Anything inside it needs to be considered a necessary cost.

And when choosing a distributor, artists definitely need to add all those extras together to find what they’re really going to pay for distribution at each provider. It’s often different than expected.